One shot won the battle

HOLY COW! HISTORY

Of all the forgotten tales I bring to life in this column, this may be the most obscure. Forgotten today, it played a key role in determining which …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Subscribe to continue reading. Already a subscriber? Sign in

Get 50% of all subscriptions for a limited time. Subscribe today.

Please log in to continueNeed an account?

|

One shot won the battle

HOLY COW! HISTORY

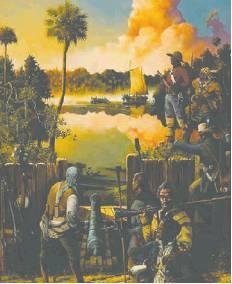

Of all the forgotten tales I bring to life in this column, this may be the most obscure. Forgotten today, it played a key role in determining which nation would control what’s now the southeastern United States. And just one cannon shot settled it.

It all started during the War of 1812. While we were battling Britain, Britain was also battling pesky Napoleon on the Continent. The Brits needed all the men they could get for their military. So in 1814 they revived the Corps of Colonial Marines.

Basically, England extended this offer to African-American slaves: fight with us and when the war is over you can live in freedom in any British possession in North America. Several hundred men took the deal and served under the Union Jack.

In fact, some 300 of those Colonial Marines supported the British forces that burned Washington and tried to capture Baltimore before being repulsed at Fort McHenry.

The war ended with General Andrew Jackson’s spectacular victory in the Battle of New Orleans.

True to their promise, the Brits helped the Colonial Marines as best they could. Although Florida was owned by Spain, Britain had built a stockade fort in the panhandle on the Apalachicola River. (With Spain contending with Napoleon too, there wasn’t much it could do.)

Hundreds of black British veterans and their families settled in and around the fort, leading to the name Negro Fort. (This was 1815, remember.) The Brits paid off the Colonial Marines, gave them the fort and its 10 cannons, wished them well and left. It soon became a mecca for runaway slaves and displaced Native Americans.

The war was over, but the Southeast remained a powder keg waiting to explode. The Americans had built Fort Scott up the same river near where modern Alabama, Georgia and Florida connect. Jackson had to keep it supplied. But sending arms up the Apalachicola meant violating Spanish sovereignty, and that could trigger a war. Having just come out of a two-year conflict with Britain that had left the capital in ashes, another war was the last thing Washington wanted. But Old Hickory didn’t mind taking the risk.

During one supply run, American boats stopped near Negro Fort and sent a party of sailors ashore to fill canteens. The free blacks and Indians opened fire, killing all but one sailor.

Jackson was furious. He asked Washington for permission to seize the fort. Waiting around for a reply wasn’t his style, so he decided to attack. When soldiers of the 4th United States Infantry surrounded the stockade, its defenders raised both the British flag and a red banner signaling they would fight to the death rather than surrender. An estimated 280 people, including women and children, were gathered within the fort’s wooden walls. More huddled outside. Barrels of gunpowder were stacked inside a structure called the powder magazine. The defenders were ready for a fight.

On the afternoon July 27, 1816, two gunboats took up position for a bombardment. A handful of cannon shots were fired to establish the range. Artillery is very loud, and the fort’s occupants were understandably terrified.

Then it happened.

Beginning the bombardment in earnest, a red hot cannonball scored a direct hit on the magazine, igniting all that gunpowder. A massive explosion ripped the little fort apart, shaking the ground and unleashing a roar that was heard in Pensacola 100 miles away.

For all practical purposes, Negro Fort no longer existed. One amazing shot had determined the battle’s outcome.

An American witness wrote, “The explosion was awful, and the scene was horrible beyond description. Our first care, on arriving on the scene, was to rescue and relieve the unfortunate beings who survived the explosion. The war yells of the Indians, the cries and lamentations of the wounded, compelled the soldier to pause in the midst of victory, to drop a tear for the sufferings of his fellow beings …”

Only 50 people in the fort survived. The other 230 were shot, burned alive or blown apart. No Americans were killed.

There would be more fighting and deaths until the United States gained control of Florida in 1819, and even afterward.

The army quickly built a new fort nearby, naming it Fort Gadsen. Its active military status lasted until a malaria outbreak made the Confederates abandon it in 1863. Florida maintains it as a state historic site.

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here