Border veteran recalls the good ol’days

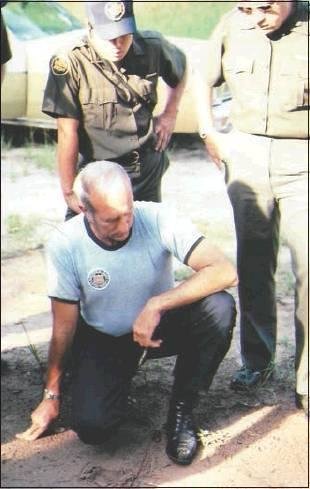

Retired Border Patrol Agent Tim Houghtaling is a former Lexington resident living in Florida. With international attention on the Mexican border now, he talks about his own experiences with Chronicle Editor Emeritus Jerry Bellune.

It was a good time on the border 40 years ago. Most Mexicans considered the Border Patrol an inconvenience and were hospitable when caught.

All agents had stories of vans stuck in farm mud …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Subscribe to continue reading. Already a subscriber? Sign in

Get 50% of all subscriptions for a limited time. Subscribe today.

Please log in to continueNeed an account?

|

Border veteran recalls the good ol’days

Retired Border Patrol Agent Tim Houghtaling is a former Lexington resident living in Florida. With international attention on the Mexican border now, he talks about his own experiences with Chronicle Editor Emeritus Jerry Bellune.

It was a good time on the border 40 years ago. Most Mexicans considered the Border Patrol an inconvenience and were hospitable when caught.

All agents had stories of vans stuck in farm mud stopping, opening the doors to unload prisoners to push the van out of the mud so they could go to jail.

Only the professional ‘coyotes’ risked criminal charges for alien smuggling or drug hauling caused an occasional problem.

I vividly remember a morning after a midnight shift in 1978 shopping in a grocery store when a green card holder – a legal immigrant– surprised me by thanking me for my service.

He said he drove 200 miles north to find a job that paid enough to support his family in San Diego.

My experience began in Detroit in 1970 when Wayne State University Public Safety hired me. I learned real policing as a Detroit police officer where every night I wondered, “who can I catch next?”

I applied for US Customs but they paid too little to support my family. The Border Patrol paid just enough to make the leap.

I began in 1977 as a border agent then a year later transferred to Detroit as a criminal investigator for the defunct Immigration & Naturalization Service.

Both were on ‘the border.’

The Detroit version had more variety – like Charleston or Raleigh – where we reminded visitors, students and temporary workers their stay had expired.

Then I traveled by bus to report for duty at Chula Vista, CA, on the border below San Diego. It was a reality check when the Greyhound driver at the door spoke to me in Spanish.

In weeks of classes we were forcefed Spanish, immigration and federal criminal law and police tactics.

Immigration law evolves constantly. Today’s agents are expected to know all customs and agriculture laws to be a Border Patrol Agent, border inspector or ICE Special Agent today.

During those months we worked at the busiest port of entry on the southern border at Imperial Beach.

On the Mexican side on Sundays we watched bulls try to gore toreadors.

At night, crowds tramped through fields of asparagus, strawberries and celery.

Irate farmers loudly protested that their plants costing $2 to $5 each were stomped to death at night.

I was young, in shape, and enjoyed the hunt.

A fun section was the security fenced Navy Seal training station that funneled large groups to where single agents could surprise, then arrest whole groups.

The East Side included loading docks above the rail tracks used daily by trains to and from Mexico. Groups waited for dusk to get past the Border Patrol and on into the interior where there was no enforcement.

At Chula we had 460 band radios which were useful only as clubs.

At that time the patrol had Vietnam war portable vibration sensors alerting them to foot traffic on paths over the gullies and hills from the border.

There were more of them than us and only 3 of 10 crossing were apprehended.

Employers were willing to hire illegal Mexicans to save the costs of workman’s comp, taxes, social security, insurance and inevitable miscellaneous expenses.

That’s why Ronald Reagan’s ‘once in a lifetime’ amnesty famously failed.

Almost before the ink was dry on that law, investigators did a sanction raid on onion farms near Atlanta. The farmers called their senators and representatives who called the INS Investigators ordering the operation terminated.

What changed was millions of Mexicans worked with falsified documents.

The INS had 1,500 agents for the whole country – less than most big cities.

The fraud was not manageable. The farmers and ranchers ignored the law.

Congress reacted to the familiar cry of farmers and ranchers complaining they can’t bring in crops unless they employed illegals.

Those who worked under the table or with false documents for years suddenly found green cards were a market advantage. They could now take more than seasonal jobs and begin their American Dream.

To provide labor for farmers, Congress passed the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Act. It didn’t cure the problem but forced all to pay the same benefits as their competitors.

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here