Boston’s great molasses flood of 1919

HOLY COW! HISTORY

Boston’s North End neighborhood had a sticky mess on its hands exactly 100 years ago. This is the centennial of the Great Molasses Flood of 1919. It …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Subscribe to continue reading. Already a subscriber? Sign in

Get 50% of all subscriptions for a limited time. Subscribe today.

Please log in to continueNeed an account?

|

Boston’s great molasses flood of 1919

HOLY COW! HISTORY

Boston’s North End neighborhood had a sticky mess on its hands exactly 100 years ago. This is the centennial of the Great Molasses Flood of 1919. It sounds funny. But this deadly tragedy was no laughing matter.

The Purity Distilling Company had a facility in the North End. When molasses is fermented it puts the kick in alcoholic beverages such as rum and the “umph” in ethanol. Purity’s plant included a large tank for storing molasses. It worked well … until January of 1919.

The weather had been all over the place that week. Temperatures were first frigidly cold, then climbed to 40º on Wednesday. Just past noon that day, rat-a-tat-tats like machine gunfire rang out. The ground shook. There was a loud roar, followed by a long rumble.

The “gunfire” was actually the sound of the giant tank’s metal rivets popping loose, sending it crashing to the ground and unleashing more than 2.3 million gallons (about 14,000 tons) of molasses.

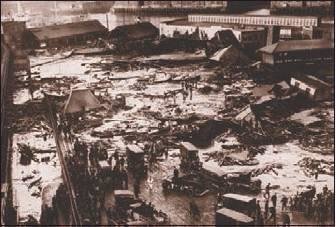

It was sheer chaos. Picture a wall of brown goo up to 40 feet tall racing along at 35 miles per hour covering everything in its path.

In those early days of autos and trucks, much freight was still delivered in horse-drawn wagons. Countless animals were swallowed up and suffocated.

Buildings were crushed, in many cases lifted off their foundation and swept away. A nearby elevated railroad line’s girders were damaged with one car tipped off the tracks. A truck was swept into Boston Harbor.

Then there were the people caught in the flood. A boy coming home from school was snatched by a wave and carried to the crest, riding it like a surfboard until plunging downward and passing out. Coming to, he opened his eyes to find his three sisters staring down at him.

Others weren’t so lucky. When quiet returned, 21 people were dead. Another 150 were injured, some seriously.

About 116 cadets from the Massachusetts Nautical School were the first help to arrive on the scene, wading through streets filled waist deep with goo while looking for survivors. They were followed by Boston Police, the Red Cross, and Army and Navy personnel. All searched the muck for four days before calling it quits.

It took weeks for the North End to return to normal. Salt water was sprayed on streets from a nearby fireboat and sand was dumped onto cobblestones. So much molasses had flowed into the harbor that it stayed brown until summer. In fact, there had been such a huge stream of sightseers and gawkers that they carried molasses home on their shoes until, as one witness described it, “Everything a Bostonian touched was sticky.”

Then came the class-action lawsuit, one of the first ever in Massachusetts, followed by three years of hearings. In the end United States Industrial Alcohol, Purity Distilling’s parent company, wound up paying $600,000 (some $6.5 million in today’s dollars) in out of court settlements.

So, what caused the disaster? To this day nobody knows for sure. Some people claimed anarchists blew up the storage tank. An inquiry found the construction chief had skipped basic safety tests when the tank was built. It leaked so badly, the company painted it brown to hide the drips. Local residents even put buckets under the tank to take home leaked molasses for themselves. It’s also possible fluctuating temperatures caused a chemical reaction inside the tank.

One thing is certain: in 2016 a team of Harvard scientists extensively studied firsthand accounts of the disaster and recreated its conditions in a lab. They confirmed the witnesses were right: the molasses tsunami was quite capable of moving at 35 mph.

Today a small plaque commemorates the tragedy and its 21 victims, who ranged in age from 10 to 78. In a city famous for venerating its history, the Great Molasses Flood of 1919 isn’t forgotten. But it seems all has been forgiven. Boston is known for baked beans after all and you can’t make them without, well, you know.

Have comments, questions or suggestions you’d like to share with Mark? Message him at jmp.press@gmail.com .

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here