‘Children of the battlefield’ were famous

MARK POWELL’S

HOLY COW!

HISTORY

It had been a terrible day. Confederate troops roared into Gettysburg, Pa. Outnumbered Union defenders …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Subscribe to continue reading. Already a subscriber? Sign in

Get 50% of all subscriptions for a limited time. Subscribe today.

Please log in to continueNeed an account?

|

‘Children of the battlefield’ were famous

MARK POWELL’S HOLY COW! HISTORY

It had been a terrible day. Confederate troops roared into Gettysburg, Pa. Outnumbered Union defenders resisted as long as they could. But the Southern tide was too strong. The Yankees retreated through the small town, shooting as they fell back.

After the battle, a little girl came upon a soldier’s body lying in a side street. That wasn’t unusual; Gettysburg was littered with seemingly countless bodies.

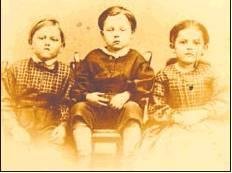

But this one was different. One hand clutched an ambrotype (a photograph printed on a glass plate) showing three young children. The soldier had obviously gazed at it as he died. The girl pried the photo from his dead grip. Not long afterward, the man was quickly buried. In that time before modern GI “dog tags” there was no way to identify him. So he was tossed into a grave and given a one-word tombstone that still haunts many Civil War cemeteries: “Unknown.”

The story might have ended there, had the girl not taken the photo home with her. She gave it to her father, who owned a tavern a dozen miles away. Benjamin Schriver was struck by the touching tableau: three small children, the last faces their dying father ever saw, who didn’t know they were now orphans.

The picture became a barroom conversation piece. Dr. John Bourns was traveling to Gettysburg to help tend the wounded. He saw the image and realized it might help identify the fallen soldier. When his medical duties were finished, he found the soldier’s grave, arranged to make sure it was properly tended, then rushed back to Philly with the photo.

A local photographer printed hundreds of copies in the carte de visite format, small paper photos about the size of modern baseball cards. Bourns sent them to newspapers across the North. Though technology didn’t yet permit photographs to be printed in newspapers, they still carried stories detailing the touching tale of the dead’s man’s ambrotype. One such article was published in The Philadelphia Inquirer on October 19, 1863, under the headline, “Whose Father Was He?” Many papers reprinted it verbatim.

One was the October 29 edition of the American Presbyterian. It found its way to tiny Portville in western New York a few days later.

In early November, Dr. Bourns received a letter from Portville’s postmaster written on behalf of Mrs. Philinda Humiston. She hadn’t heard from her husband since before the Battle of Gettysburg and asked to see the photo. Bourn rushed her a copy.

Philinda tore open the envelope. The faces of 8 year-old Franklin, 6 year-old Alice, and 4 year-old Frederick stared back at her. They were her children. The dead soldier was her husband, 33-year-old Sergeant Amos Humiston of the 154th New York Infantry. The American Presbyterian published news of the father’s identity on November 19—the same day Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address.

People around the North clamored to see the touching image of the children. Soon copies were being sold at photography studios under the title The Children of the Battlefield. It was also the name of a popular song. Many poems were written, too.

On January 2, 1864, Philinda Humiston welcomed Dr. Bourns into her home in Port-ville. He gave her the original ambrotype, still stained with her husband’s blood. “Her hands shook like an aspen leaf,” he wrote later, “but by strong effort she retained her composure.” He also presented her with profits from The Children of the Battlefield photo sales.

As for the children themselves, Frank eventually graduated from Dartmouth and was a popular doctor in New Hampshire until his death in 1912. Fred was a successful grain merchant in Massachusetts, dying in 1918. Poor Alice was a lost soul, never marrying, drifting from job to job and living with relatives until she died when her dress caught fire in 1933. Having been thrust into the spotlight so early, all three children refused to talk about the photo in later life.

In 1993, a statue commemorating Amos Humiston was unveiled near the spot where he died. He’s the only individual enlisted man from that massive battle so honored. He rests today under a tombstone bearing his name and unit in Grave 14, Row B in Gettysburg’s famous National Soldiers Cemetery. Some 979 others weren’t so fortunate; their stones simply say “Unknown.” A single photo spared Amos Hummiston from making it 980.

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here