HOLY COW! HISTORY: Lincoln’s forgotten duel

President Abraham Lincoln and his wife were chatting with Union officers. One asked, “Is it true you once went out to fight a duel for the sake of the lady by your side?” Lincoln …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Subscribe to continue reading. Already a subscriber? Sign in

Get 50% of all subscriptions for a limited time. Subscribe today.

Please log in to continueNeed an account?

|

HOLY COW! HISTORY: Lincoln’s forgotten duel

President Abraham Lincoln and his wife were chatting with Union officers. One asked, “Is it true you once went out to fight a duel for the sake of the lady by your side?” Lincoln answered, “I do not deny it. But if you desire my friendship, you will never mention it again.” The conversation changed pronto.

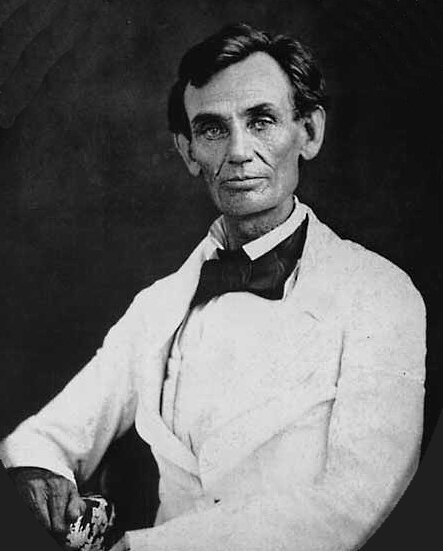

Nearly 20 years before reaching the White House, Lincoln was indeed involved in an “affair of honor.” Given the response you just read, it’s no surprise you’ve probably never heard of it before.

Here’s what happened when Abe Lincoln fought a duel.

Summer 1842. Lincoln was an up-and-coming attorney in Springfield, Illinois’ rough and tumble state capital. His on-again, off-again courtship of vivacious Kentucky belle Mary Todd was on again. Things looked bright for the lanky 33-year-old state representative.

For years, Whig Lincoln had a friendly working relationship with a fellow representative, Democrat James Shields.

When Shields became state auditor, things soured. Shields stopped accepting Illinois’ paper money as payment for taxes, creating hardship for farmers and working people. Lincoln and Shields parted ways over it.

And as so often happens in these situations, things quickly turned personal.

Lincoln put his dispute with Shields into words. Anonymously, which was an accepted practice at the time. Shields was known around Springfield for being pompous, quirky, even vain. And Lincoln went at him mercilessly in a letter to the local newspaper.

“Dear girls, it is distressing, but I cannot marry you all,” Lincoln had Shields fictitiously saying. “Too well I know how much you suffer; but do, do remember, it is not my fault that I am so handsome and so interesting!”

Lincoln let Mary read his letter first. She thought it was a hoot, even suggesting good barbs for a follow-up.

But Lincoln didn’t write the next letter. Mary did.

Without telling her boyfriend, she wrote under the pen name “Cathleen” and took mocking Shields to a whole new level, pushing him over the edge.

He stormed into the paper’s office, demanding to know who authored the letters. Lincoln had instructed the editor in advance that if Shields asked, his identity should be revealed. But that was before Mary got in on the act. Wanting to protect her from controversy, he accepted responsibility for both.

Shields wrote a letter of his own. It said, “I have become the object of slander, vituperation, and personal abuse. Only a full retraction may prevent consequences which no one will regret more than myself.”

Lincoln returned Shields’ letter, demanding that he be addressed in “a more gentlemanly manner.”

Shields responded the way men in 1842 often did. He challenged Lincoln to a duel.

Abraham Lincoln had many qualities, but cowardice wasn’t one of them. Yet, he thought dueling was ridiculous, and this one especially so.

Dueling was illegal in Illinois, but it wasn’t in nearby Missouri. So, the two agreed to meet on Bloody Island in the Mississippi River near St. Louis. It was close to Alton, Ill., yet safely across the state line.

As the challenged party, Lincoln selected heavy cavalry broadswords as the weapons. Because he stood 6’4” and his opponent was only 5’9”, Lincoln felt the cumbersome swords gave him an advantage. "I didn't want the damned fellow to kill me,” the future president recalled later, “which I think he would have done if we had selected pistols.”

Both men were popular in Springfield. It seemed half the town’s population traveled to Alton on Sept. 22 to witness the encounter. They waited anxiously as the two principals and their seconds headed to Bloody Island.

The mood was tense as the men faced each other. Without warning, Lincoln hoisted his broadsword over his head, lopping off an overhead tree branch.

Shaken, Shields wanted to go ahead with the duel. But his friends didn’t. They pulled him aside and probably said something like, “Did you see that? He’ll kill you. Call it off!”

A face-saving compromise was quickly reached. Lincoln did a mea culpa and accepted responsibility for everything. Shields swiftly accepted. The matter was settled. But Lincoln being Lincoln, it couldn’t end without a bit of humor.

As people back on the riverbank eagerly awaited word, a boat came into view. They were horrified to see a bloody body slumped over the bow. Folks ran toward it as the boat docked.

Up close, they found a log with a bright red shirt pulled over it. Lincoln and Shields appeared on the dock, howling in laughter. The crowd joined in, and everyone went home happy as clams.

The two men remained on good terms for the rest of their lives. Shields went on to serve as a U.S. senator and general in the Civil War.

And Lincoln ... well, you know how his story turned out.

As far as great duels go, Lincoln-Shields doesn’t rank up there with the Burr-Hamilton. But in spite of its absurdity, it teaches an important lesson today.

Two people can overcome any difference if they’re willing to meet halfway. With no trip to Bloody Island required.

Have comments, questions or suggestions you’d like to share with Mark? Message him at jmp.press@gmail.com.

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here