The man who said ‘no’ to Hitler

HOLY COW! HISTORY

Every dictatorship shares one thing in common: unquestioning, blind obedience to the dictator from his subjects. Whether it’s the Castros’ Cuba, …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Subscribe to continue reading. Already a subscriber? Sign in

Get 50% of all subscriptions for a limited time. Subscribe today.

Please log in to continueNeed an account?

|

The man who said ‘no’ to Hitler

HOLY COW! HISTORY

Every dictatorship shares one thing in common: unquestioning, blind obedience to the dictator from his subjects. Whether it’s the Castros’ Cuba, Kim Jongun’s North Korea or Stalin’s Russia, it’s always the same – when the Boss says “Jump!” you ask, “How high?”

But in the closing days of World War II, one German not only said “no” to Hitler’s face, he even lived to tell about it.

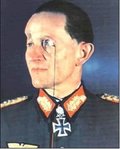

Dietrich von Saucken was the living personification of the Prussian military stereotype: coldly humorless, ramrod straight, shiny black boots, smugly looking down his nose while wearing, of course, the obligatory monocle.

Born Friedrich Wilhelm Eduard Kasimir Dietrich von Saucken in Prussia, his father was a well-connected official in Imperial Germany. The boy showed promise as an artist; his mother and school principal encouraged pursuing it. But his father said, “Nein!” He wanted his son to be a soldier.

So Dietrich dutifully enlisted in the German army – just in time for World War I.

When the guns fell silent in 1918, he was a captain with multiple medals and a reputation for personal bravery. He stayed in the army during the 1920s and 30s and was a colonel when World War II erupted.

Von Saucken kept rising in rank as the units he commanded grew bigger. He eventually earned a reputation as a tough general who got the job done.

But in 1945, when the Third Reich was on its last legs; Von Saucken committed a huge no-no by publicly saying the war was unwinnable. He was promptly benched in the Reserves.

But with the Russians barreling toward Berlin from the East, and the Americans, British and Canadians closing in from the west, Hitler had to have him back. So on March 12, he was summoned to Berlin for his new orders.

Von Saucken sauntered into Hitler’s presence reeking of disrespect. He wore his sword (officers were not allowed to bring weapons to meetings with the Fuhrer after the failed assassination attempt the previous July) and didn’t remove his monocle. He gave an indifferent military salute, rather than the official German Greeting, the outstretched arm accompanied by an enthusiastic “Heil Hitler.”

Incredibly, Hitler didn’t seem to notice. He told von Saucken he was to immediately fly to East Prussia (modern Poland) and take command of the Second Army.

Then he casually added, “and you will report to Gauleiter Forster.” A gauleiter was like a civilian governor of a state, always a fanatical Nazi Party flunky and a Hitler bootlicker.

Von Saucken gave a sneer that said, “Are you kidding me?” But Hitler didn’t see it; his attention was riveted on a battle map. Von Saucken slapped his hand on it. That got the Fuhrer’s attention.

The general looked him straight in the eye and said, “I have no intention, Herr Hitler, of taking orders from a gauleiter!”

Hearts froze around the room. Von Saucken had gone too far by saying “Herr Hitler” (the civilian “Mr. Hitler”) rather than the required “Mein Fuhrer” (“My Leader”). The generals braced for a hysterical outburst that would surely end with von Saucken being hauled out of of the bunker, stood against a wall and shot.

Hitler was quiet. Then, to the utter amazement of everyone, he softly said, “Alright Saucken, have command of it yourself.” He dismissed the rebellious general with a hand wave.

In one final blast of disrespect, von Saucken gave a very tiny bow (instead of the Nazi salute), spun about on his heels and stormed off to his new command.

Nothing was said about his defiance of The Leader.

Von Saucken fought tenaciously in the war’s dying days. As the end neared, he was provided an airplane so he could fly to the west and surrender to the more compassionate Americans. Von Saucken refused; he would stay and suffer the same fate as his men with the Soviet victors.

Hitler committed suicide on April 30. On May 8, the Third Reich went out of business. One of its final official acts that day was awarding von Saucken the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds, Nazi Germany’s highest battlefield medal, the very last of its 27 recipients.

Von Saucken surrendered to the Soviets the next day, and they lived up to their reputation for brutality. They beat him so savagely that when he was released from prison in 1955, he was confined to a wheelchair and in intense pain until his death in 1980.

Dietrich von Saucken was no hero, nor should he be honored with the respect given today to the German officers who gave their lives trying rid the world of Hitler.

Still, one has to admire his courage.

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here